The Abdication of Nicholas II: 100 Years Later

The following is a Legitimist examination of the 2 March 1917 (15 March 1917, new style) abdication of Nicholas II and the subsequent 3 March 1917 (16 March 1917, new style) deferral of the throne by Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Emperor Nicholas II's laying down of "the supreme power."

On July 15, 2015, Natalia Poklonskaya, the then Prosecutor of the Republic of Crimea, stated that the abdication of Nicholas II had no legal effect.

She declared that the abdication was invalid because it had been signed in pencil. “This piece of paper, which in history textbooks has been represented as a supposed act of abdication, has no legal validity. This scrap of paper, signed in pencil and violating all the necessary legal and procedural methods and format, has no legal force.” 1

Poklonskaya’s baseless assertion that the abdication of the Emperor is invalid because it does not comply with contemporary Russian legal norms is typical of one type of argument that for 100 years has surrounded the abdication and subsequent deferral of the throne. It is important to look at the act of abdication entirely within its own legal context – that of the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire.

Nicholas II regarded his abdication for himself and for his son as wholly binding and legal. Count Fredericks, who countersigned the abdication as a witness, regarded and accepted the act as binding and legal. Both the Imperial Duma and the Grand Duke Michael, into whose hands the Imperial power passed, regarded the act as binding and legal. There was no doubt at the time that it was the intention of Nicholas II to abdicate for himself and for his son, and to pass the throne to his younger brother, the Grand Duke Michael. They all regarded the abdication this way because they all understood the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, which provided the legal possibility for Nicholas II to abdicate.

The Russian Legitimist subscribes to and follows the legitimist principle that only within the context of the dynastic laws of the reigning house may dynastic questions be answered. Contemporary historians will regard the abdication solely as a political act demanded by expediency, but The Russian Legitimist looks at the abdication from another perspective--that of a dynastic act taken (or not taken) in accordance with the Fundamental Laws and the Statute on the Imperial Family.

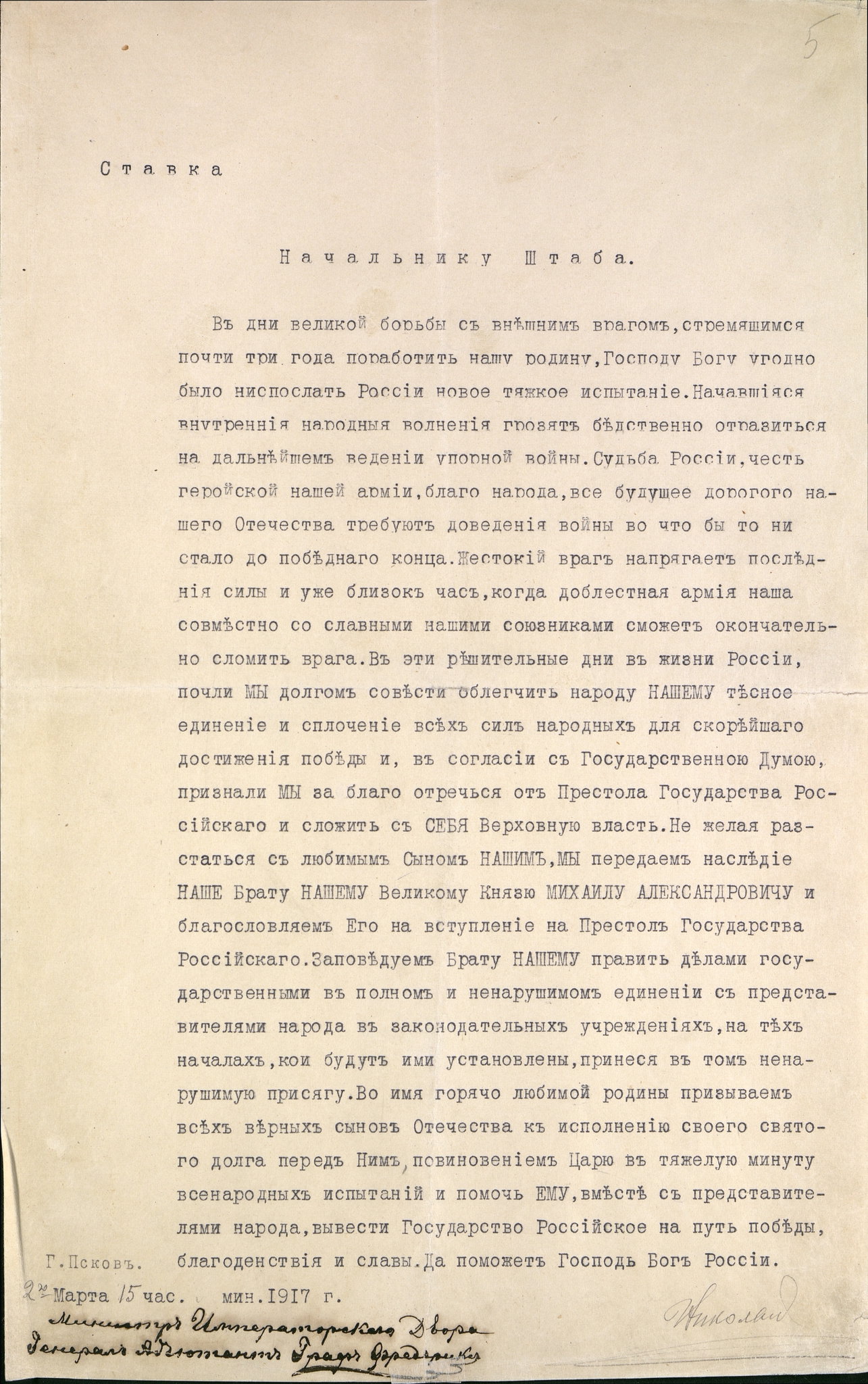

In this article, published on the 100th anniversary of the abdication of Nicholas II, The Russian Legitimist attempts to answer from a purely legitimist perspective the issues surrounding the act of abdication and deferral. We can begin by looking at the text of the original documents:

THE ABDICATION OF EMPEROR NICHOLAS II

2/15 March, 1917, 3:00pm, Pskov

In the days of the great struggle against the foreign enemies, who for nearly three years have tried to enslave our fatherland, the Lord God has been pleased to send down on Russia a new heavy trial.

Internal popular disturbances threaten to have a disastrous effect on the future conduct of this persistent war. The destiny of Russia, the honour of our heroic army, the welfare of the people and the whole future of our dear fatherland demand that the war should be brought to a victorious conclusion whatever the cost.

The cruel enemy is making his last efforts, and already the hour approaches when our glorious army together with our gallant allies will crush him. In these decisive days in the life of Russia, We thought it Our duty of conscience to facilitate for Our people the closest union possible and a consolidation of all national forces for the speedy attainment of victory.

In agreement with the Imperial Duma We have thought it well to renounce the Throne of the Russian Empire and to lay down the supreme power. As We do not wish to part from Our beloved son, We transmit the succession to Our brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, and give Him Our blessing to mount the Throne of the Russian Empire.

We direct Our brother to conduct the affairs of state in full and inviolable union with the representatives of the people in the legislative bodies on those principles which will be established by them, and on which He will take an inviolable oath.

In the name of Our dearly beloved homeland, We call on Our faithful sons of the fatherland to fulfil their sacred duty to the fatherland, to obey the Tsar in the heavy moment of national trials, and to help Him, together with the representatives of the people, to guide the Russian Empire on the road to victory, welfare, and glory.

May the Lord God help Russia!

(SIGNED)

NICHOLAS

(COUNTER-SIGNED)

FREDERICKS, MINISTER OF THE IMPERIAL COURT

Did the Emperor have the right to abdicate?

Yes.

In the Fundamental Laws, Chapter three, sections 37 and 38 state clearly:

37 As the rules on the order of succession, enunciated above, take effect, a person who has a right to succeed is free to abdicate this right in those circumstances in which an abdication does not create any difficulty in the following succession to the Throne.

38 Such an abdication, when it has been made public and becomes law, is henceforth considered irrevocable.

It is clear from these sections that the Fundamental Laws a) allow abdication by any dynast as long as that abdication does not place the succession in jeopardy, and that b) once that abdication has been made public and becomes law it is not only valid, but irrevocable.

The Fundamental Laws do not provide any specific language for an instrument of abdication, but we may understand and accept that the text of the abdication document clearly states: “In agreement with the Imperial Duma We have thought it well to renounce the Throne of the Russian Empire and to lay down the supreme power.” This may be regarded as a conclusive statement of renunciation of the throne.

Was the abdication process followed in accordance with the fundamental laws?

No.

Chapter Three, Section 38 states “Such an abdication, when it has been made public and becomes law…” causes us to refer back to the Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire, Chapter Nine, “On Laws.” What was a law in the Russian Empire, and how were they made? We look at Sections 95 and 97 for clarification:

95 To inform the general public, laws are promulgated by the Governing Senate according to established procedures and do not take effect before their promulgation.

97 Upon promulgation, the law becomes effective from the time specified by the law itself, if such a period of time is not specified -- from the day on which the Senate publication containing the printed law is received locally. The law being published may itself indicate that by means of telegraph or courier it be transmitted for execution before its publication.

Section 95 has not been fulfilled. While Nicholas’ abdication was executed with the cooperation of some members of the Duma in a train car near Pskov, and the abdication was published in all the major newspapers, the instrument of abdication was never officially published by the Imperial Senate. There was no question that the abdication was accepted by the Imperial Government, and that the Emperor had complied with the terms set down for his abdication by the Fundamental Laws, but the government did not follow through with the appropriate processes.

Had the Imperial Government (or their successor, the Provisional Government) survived, no doubt the law would have been duly recorded and officially promulgated according to the letter of the law, but as section 96 clearly states, “The law being published may itself indicate that by means of telegraph or courier it be transmitted for execution before its publication.” This indicates that by virtue of its unofficial publication, the instrument of abdication could be accepted and would have had already taken effect, by the time of its promulgation, and that Nicholas II was no longer Emperor.

Did the Emperor have the right to abdicate on behalf of his son?

No.

Nicholas II was motivated by a father’s love for a very ill child whose life expectancy might be limited. No doubt presuming that he and his immediate family would leave Russia for a place of exile, possibly England, the Emperor wanted his beloved son to remain with him and the Empress in their exile. But, absent misconduct of some kind by the affected dynast, the Fundamental Laws make no provision allowing the Emperor or a parent to strip a dynast, whether a minor or not, of his succession rights. Instead, the affected dynast himself would have to abdicate his rights, and it is difficult to see how he could do so before attaining his majority.

The Fundamental Laws clearly state in Chapter Two “On the Order of Succession to the Throne,” Article 28:

28 Accordingly, succession to the Throne belongs in the first place to the eldest son of the reigning Emperor, and after him to all his male issue.

By virtue of this law Nicholas II acted in violation of the Fundamental Laws and against his oath to uphold them. This does not mean that the act of abdication on Alexei’s behalf was not considered and accepted as legal at the time, but it does mean that from a legitimist perspective, the Emperor acted illegally on this point in bypassing the legal heir, no matter what his physical condition. The fundamental laws as written by Emperor Paul I state clearly that “the heir should be determined by the law itself,” not by the whim of the Sovereign. 2

At the very moment that Nicholas II ceased to be Emperor, Tsesarevich and Grand Duke Alexei succeeded as Emperor Alexei II, under a “Regency” defined by the fundamental laws, as he was only 13 and had not yet attained his dynastic majority (for the heir, 16 years of age).

Were there legal provisions for a Regency? What were they?

Yes.

In Chapter Three, “On the attainment of Majority of the Sovereign Emperor, on Regency and Guardianship” the points surrounding the regency and guardianship are cited in detail and worth enumerating and discussing point by point:

40 Sovereigns of both sexes and the Heir to the Imperial Throne reach their majority at the age of sixteen.

Tsesarevich and Grand Duke Alexei was 13 years of age at the time of the abdication. As a result, the Regency clause would have gone into effect.

41 When an Emperor younger than this age ascends to the Throne, a Regency and a Guardianship are instituted to function until this majority is attained.

Everyone familiar with the Fundamental Laws had assumed that the much beloved heir who had so distinguished himself with his father in the period of 1914-1917 would succeed as a boy-emperor with a Regency headed by the Emperor’s brother, Michael. Several of the Grand Dukes (Paul, Kirill, and Michael) as well as some members of the Duma (Rodzianko) were surprised at Nicholas’s bypassing of the young Tsesarevich.

42 The Regency and the Guardianship are instituted jointly in one person or separately, in which case one person is entrusted with the Regency and the other with the Guardianship.

43 The appointment of Regent and Guardian, either jointly in one person or separately in two persons, depends on the will and discretion of the reigning Emperor who should make this choice, for greater security, in the event of His demise.

At the birth of the Heir, Nicholas II named the former Heir, his brother the Grand Duke Michael, as both Regent and Guardian should anything befall him. The first time there was any serious difficulty arose when Nicholas II was taken ill with typhoid at Livadia in 1900. The Empress delicately enquired with Court Chamberlain A.A. Mossolov as to whether there was any chance that Grand Duchess Olga might be named Regent, or named to the Regency council. It was determined that the Grand Duchess could not, with so many male heirs readily available within the family, but the Emperor recovered and there was no further thought of any difficulties surrounding this until 1912, when Grand Duke Michael married the twice-divorced Natalia Sheremetevskaya Wulffert against the Fundamental Laws and the order of the Emperor.

The Grand Duke Michael was quietly stripped of his Regency of the heir as one of his punishments, and he was never officially reinstated as Regent.

44 If no such appointment was made during the lifetime of the Emperor, upon His demise, the Regency of the State and the Guardianship of the Emperor who is under age, belong to the father and mother; but the step-father and step-mother are excluded.

This clause placed the Emperor in a difficult position. With himself removed as Emperor, he might have hoped that the Regency would fall to him and to his wife, the Empress Alexandra. Perhaps the Emperor realized that given their combined unpopularity, there would be no way that the Duma would have accepted the former Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra as regents for their child.

45 When there is no father or mother, then the Regency and Guardianship belong to the nearest in succession to the Throne among the underage Emperor’s relatives, of both sexes who have reached majority.

With this clause, the Emperor must have realized that even without appointment to the Regency, and even in spite of his unpermitted morganatic marriage, the Grand Duke Michael could not be stripped of his right as next most senior male dynast to serve as Regent for the young Emperor, and that he was, in fact, the heir to the throne after the childless Tsesarevich Alexei.

Did the Emperor have the right to pass the “supreme power”

to his brother Grand Duke Michael?

No.

While Nicholas’ act was accepted by the Duma, it was not legal under the terms of the Fundamental Laws, which do not allow the throne to pass in any other manner than the accepted semi-salic descent from the last Sovereign. At the time of the Abdication, the first five dynasts in line to the throne were Tsesarevich Alexei, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich, Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich, and Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich.

The entire purpose of the Fundamental Laws of the Emperor Paul I was to ensure the stability of the Russian throne, which until his accession had not been stable. Peter I’s law of succession allowed the Sovereign to choose his successor. Paul’s own mother had usurped the throne from his father, and then placed herself at the helm of government, bypassing her own son after her husband’s death. Paul was firm in his insistence that for the tranquility and safety of the Imperial Family, the laws of succession must be vested not in the whim of the Sovereign, but in the laws themselves.

Was Grand Duke Michael ever actually Emperor?

No.

From the legitimist perspective, the throne passed to the Tsesarevich Alexei (de jure Emperor Alexei II) immediately upon the abdication of Nicholas II. Even if Michael HAD inherited the “supreme power” from his brother Nicholas II, his subsequent act, the publication of his Manifesto of deferral, was also in violation of the Fundamental Laws, because the throne can never be vacant.

Did Grand Duke Michael abdicate?

No.

The Grand Duke Michael signed a manifesto of “deferral.” Carefully composed by the legal genius Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (4.), the manifesto of Michael Alexandrovich neatly avoided the irregularities which were created by Nicholas’ instrument of abdication, which, as we have seen, in several points had gone against the Fundamental Laws. It is worth looking at the text of the “Manifesto” of March 3/16 in toto:

A heavy burden has been laid on me by my brother's will in transferring to me the imperial throne of All Russia at a time of unprecedented war and unrest among the people.

Inspired by the thought common to the whole nation, that the well-being of our homeland comes above all, I have taken the hard decision to accept supreme power only in the event that it shall be the will of our great people, who in nationwide voting must elect their representatives to a Constituent Assembly, to establish a new form of government and new fundamental laws for the Russian State.

Therefore, calling on God's blessing, I ask all citizens of the Russian State to obey the provisional government which has been formed and been invested with complete power on the initiative of the State Duma, until a Constituent Assembly, to be convened in the shortest possible time on the basis of general, direct, equal, secret ballot, expresses the will of the people in its decision on a form of government.

(SIGNED)

MIKHAIL

3/III - 1917, Petrograd.

In this manifesto, Nabokov skillfully glossed over the potentially illegal transfer of power from Nicholas to Michael by having the Grand Duke take the very democratic act of placing the decision of whether he was going to reign or not into the hands of an as-yet unconvened “Constituent Assembly,” which would be assembled by an election held “on the basis of general, direct, equal, secret ballot.” This election would set in place a new government which would decide whether he was to become Emperor, or if Russia would have an Emperor at all.

No doubt, Michael, Rodzianko, Nabokov, and all those involved pinned their hopes on this new representative legislative body to decide whether Russia would continue to be monarchy. In any case, in the person of the temporarily empowered Grand Duke Michael, the Imperial House had placed its fate legally into the hands of the Provisional Government and an as yet unelected Constituent Assembly.

The provisional government would not hold, the elections would never take place for the Constituent Assembly, and the government fell in October.

So, in light of all this, who succeeded to the throne on Nicholas II’s abdication?

The Tsesarevich and Grand Duke Alexei succeeded to the throne as Emperor Alexei II, with his uncle Grand Duke Michael as Regent.

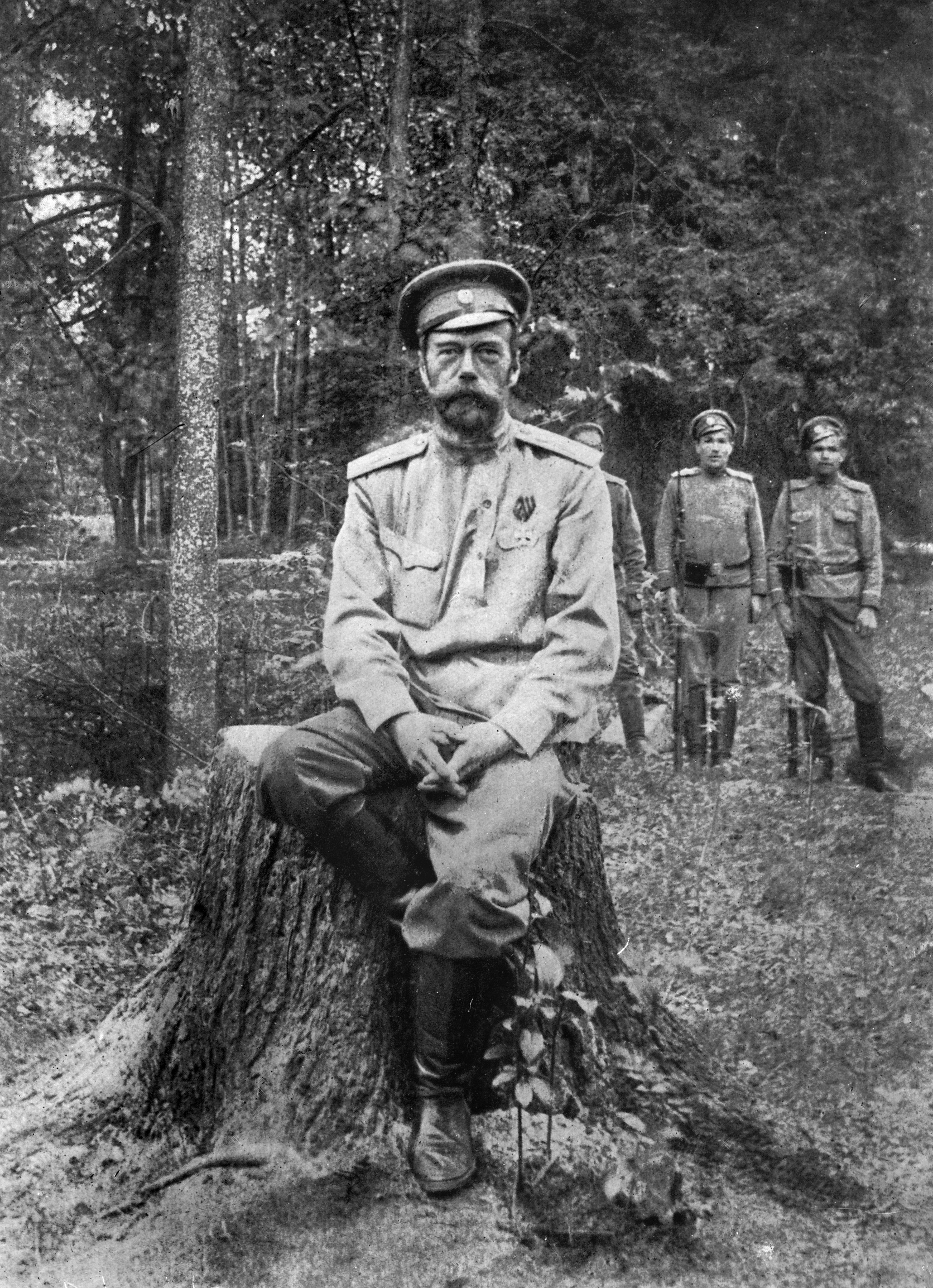

The first member of the Imperial Family to be murdered was the Grand Duke Michael, on the night of May 31/June 13, 1918, in Perm. On the following night, the former Emperor Nicholas II and his son the (de jure) Emperor Alexei II were murdered together with their family and those who were with them in Ekaterinburg.

The surviving senior male of the family was the Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich who fled north of the capital to the Grand Duchy of Finland, where his son, Prince of the Imperial Blood (later Grand Duke) Wladimir had been born in August 1917, on Russian soil. (Finland declared its independence on December 6, 1917.) Grand Duke Kirill and his family never voluntarily left Russia, but found that instead of crossing the border, the border had crossed them, making them inadvertent and unwilling exiles from their country.

On his accession to the rights of the head of the House, Grand Duke Kirill wrote to the Dowager Empress, who, hoping her sons and grandson were still alive, had stated she felt the proclamation "premature."

Dear Aunt Minnie!

Motivated only by My conscience, I issued the Manifesto in question.

If a miracle occurs, as You believe it has, that Your beloved Sons and Grandchildren should prove to be alive, then I would be the first to declare Myself immediately the faithful subject of My Legitimate Sovereign and I will lay all my actions down at His feet.

You ascended the Throne during the days of the most glittering Russian glory, as the Consort of one of our great Emperors, and You should now give to me Your blessing as I take upon myself the weighty responsibility of Imperial service that has been interrupted by the great trouble in Russia, and in the circumstances of a Throne that is overthrown and a Russia that now lies trampled down.

In such difficult circumstances, I am accepting only the duties of Your Son, and from now on, My life will be one of continuous martyrdom.

I fall down before Your feet with a son’s love. Do not abandon me at this most trying moment in My life, a moment unlike any our Ancestors have ever had to endure.

Yours affectionately, Kirill 5.

The Grand Duke Kirill later wrote to his cousin, Nicholas II's sister, Grand Duchess Ksenia Alexandrovna: "Nothing can be compared to what I shall now have to endure on this account, and I know full well I can expect no mercy from all the malicious attacks and accusations of vanity." 6.

With the exception of the Grand Dukes Nicholas and Peter Nikolaevich, and Peter's son Prince Roman Petrovich, on the discovery of the deaths of Nicholas, Alexei, and Michael, all of the members of the Imperial Family recognized Grand Duke Kirill as the Head of the House of Romanoff.

Footnotes

1 «Копия бумаги, которую в учебниках по истории преподносили как якобы отречение от власти, не имеет никакого юридического смысла. Это копия бумажки, подписанная карандашом, без соблюдения всех юридических и процессуальных необходимых процедур, форм, поэтому эта бумага не несет в себе никакой юридической силы». cf: https://lenta.ru/news/2015/07/15/abdication/ (retrieved 3/7/2017)

2 PSZ, series 1, 6:588, no. 17.910 (5 April 1797)

3. Mossolov, A.A. (Pilenco, AA ed., E.W. Dickes trans.), "At the Court of the last Tsar, Being the Memoirs of A.A. Mossolov." London: Methuen, 1935, See also, Harris, Carolyn, "The Succession Prospects of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1895-1918)" Canadian Slavonic Papers, Vol. 54 1/2, March 1, 2012.

4. Vladimir D. Nabokov (1870-1922) was born into an aristocratic family of legal scholars and practitioners. His father Dmitry had been a respected Justice Minister in the reign of Alexander II, and his uncle Konstantin Nabokov had helped craft the Portsmouth Treaty of 1905 after the end of the Russo-Japanese War. V.D. Nabokov studied criminal law at the University of St. Petersburg, and was a professor at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence.

5. http://www.imperialhouse.ru/en/dynastyhistory/dinzak3/1110.html (retrieved 3/10/2017)

6. Grand Duke Kirill, "My Life in Russia's Service," London: Selwyn & Blount, 1939., p.222